Shakespeare Tower, Barbican

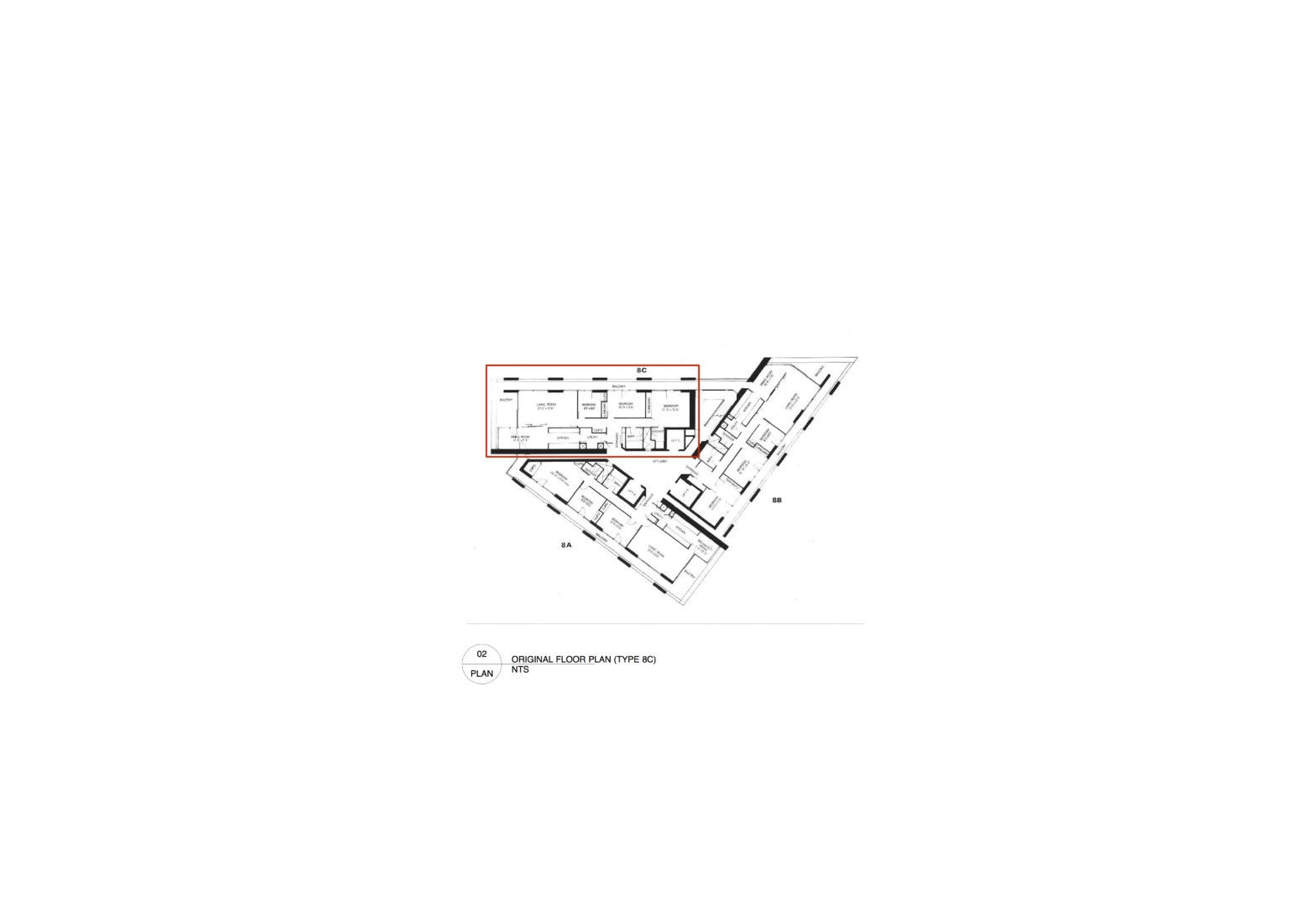

We were asked if we could convert an existing apartment into spaces, which contained some of the characteristics and atmosphere of traditional Japanese homes. The existing apartment was a type 8C in the Barbican’s Shakespeare tower contributing to a brief, which was rich in architectural references.

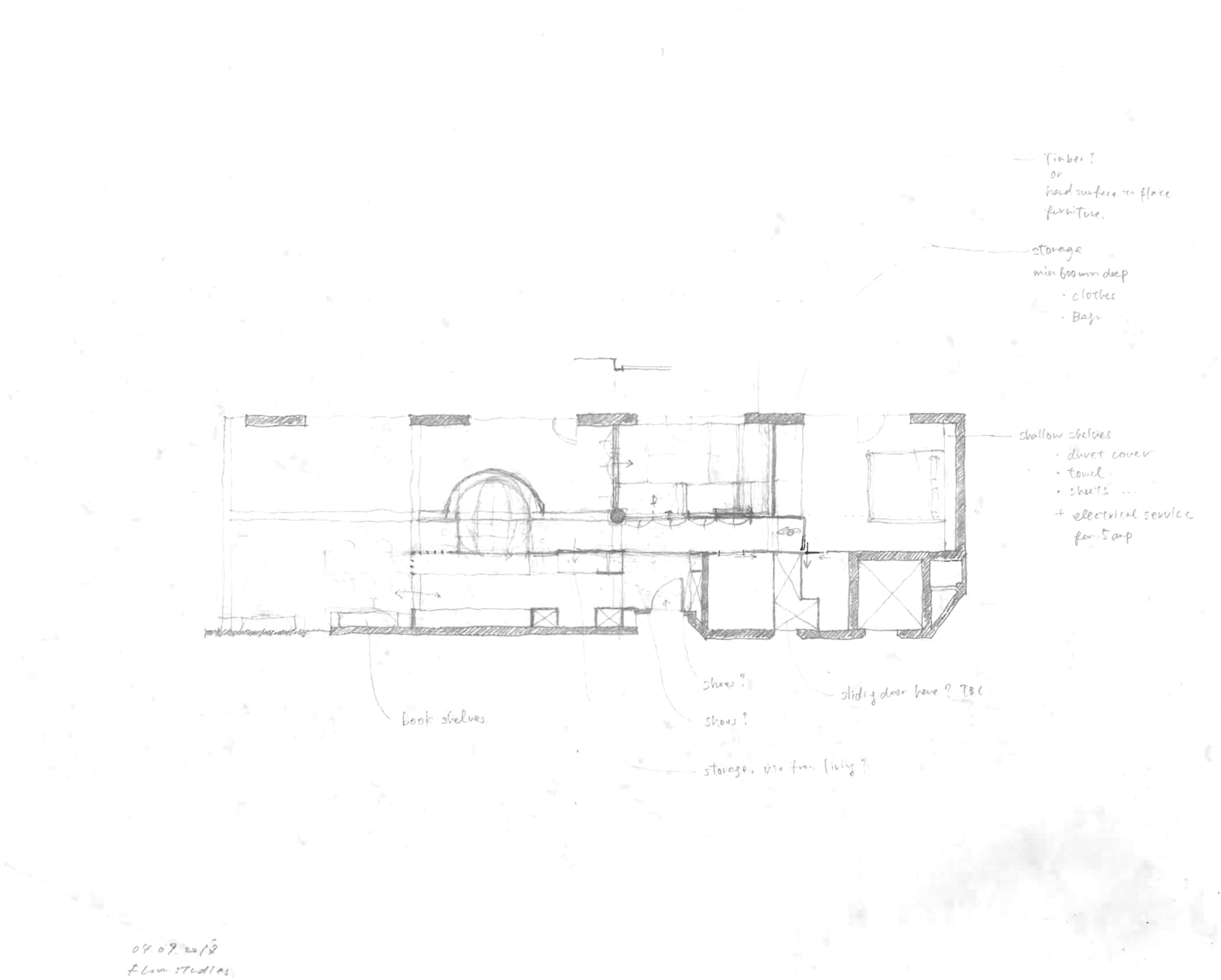

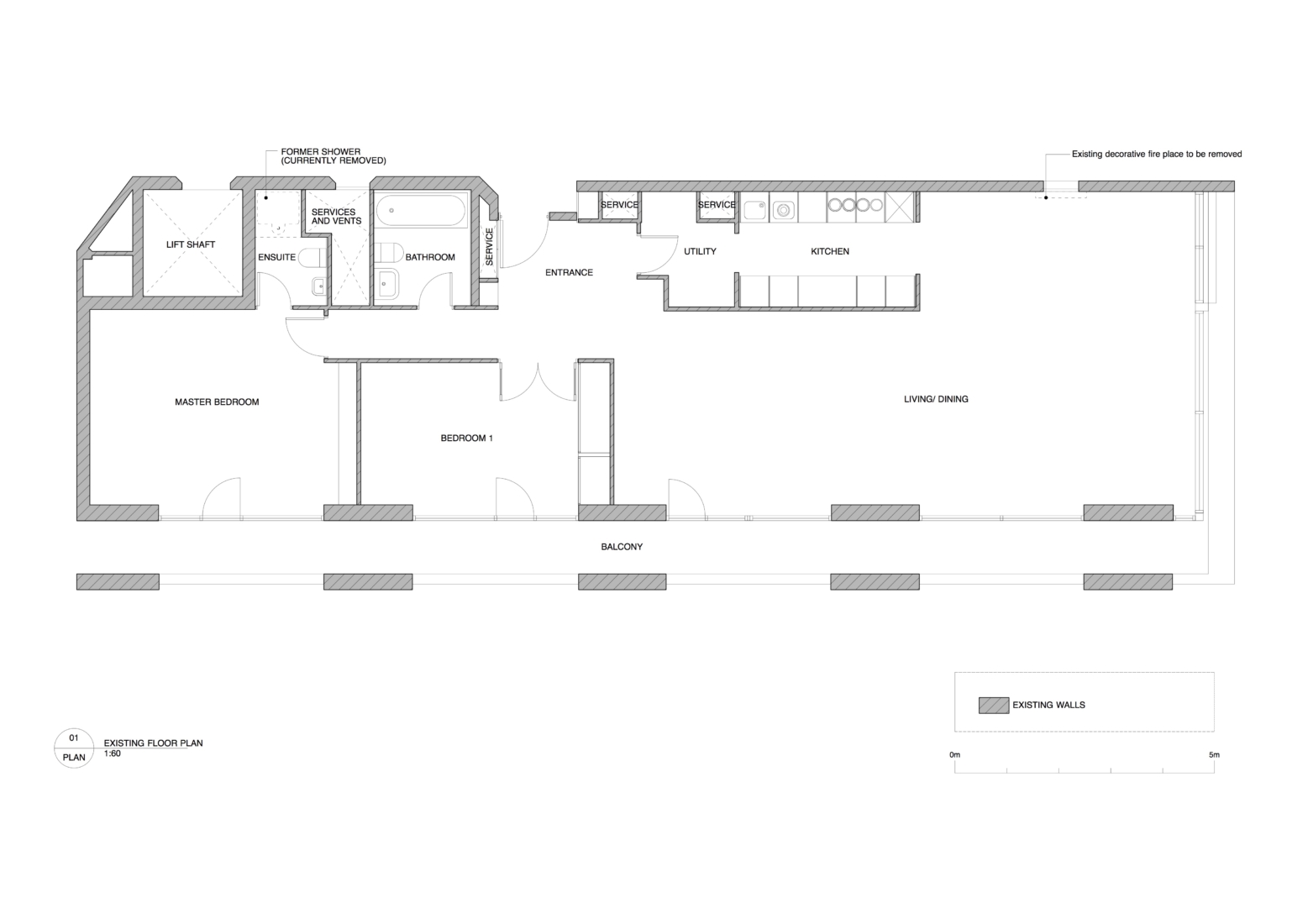

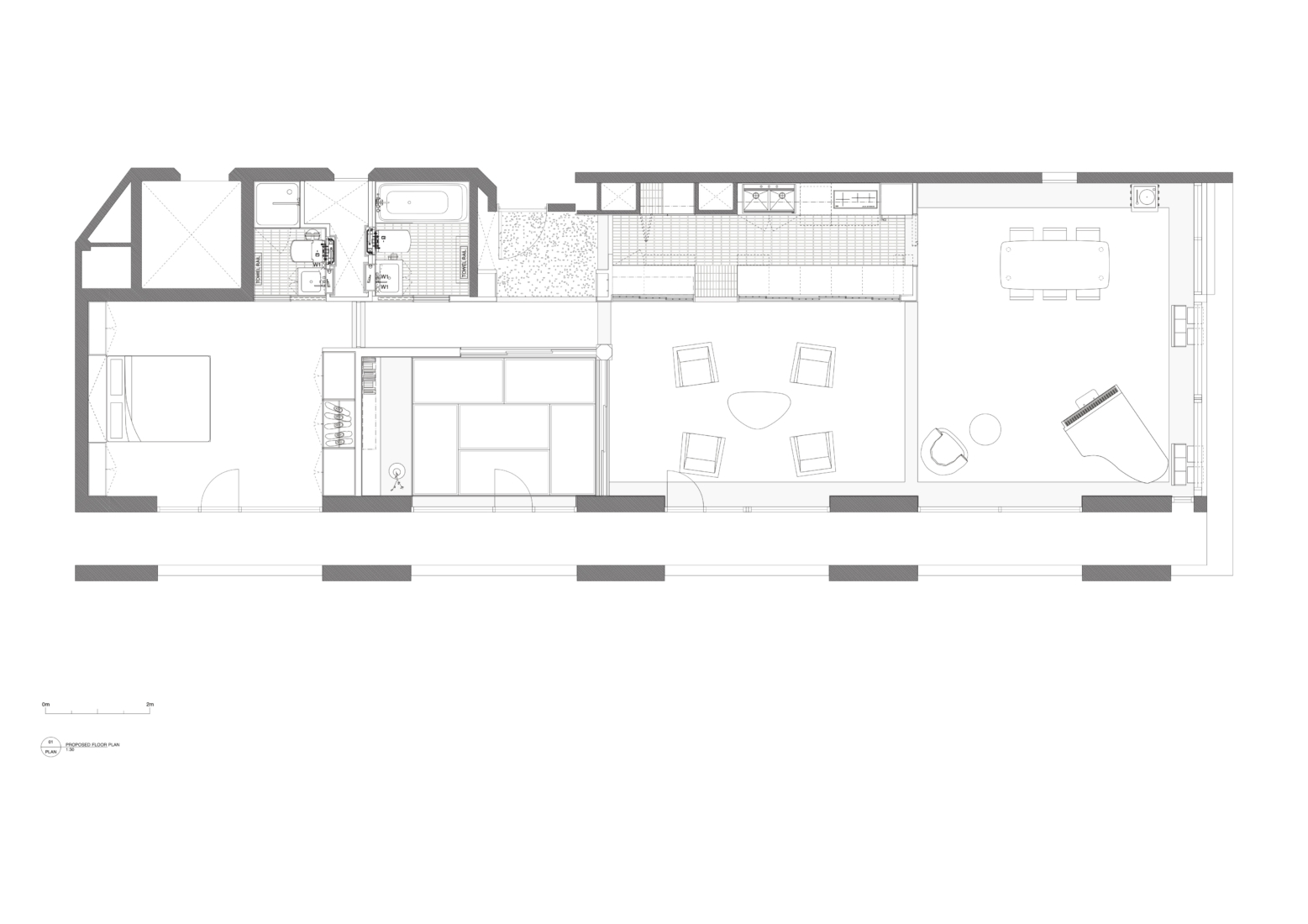

Spatially the 2 bedroom apartment had already been altered from the original design to now enclose the balcony adding internal floor area to the living/dining room. The clients asked us to open up the plan further and increase the permeability of the spaces whilst relaxing the function of some spaces. This resulted in a full strip out, revealing and retaining significant original features where possible followed by a full refurbishment. The accommodation consists of an open plan living/dining kitchen area which has a further ‘japanese room’ adjacent which can be opened up via sliding screens. The master bedroom, en-suite and larger bathroom complete the schedule of accommodation.

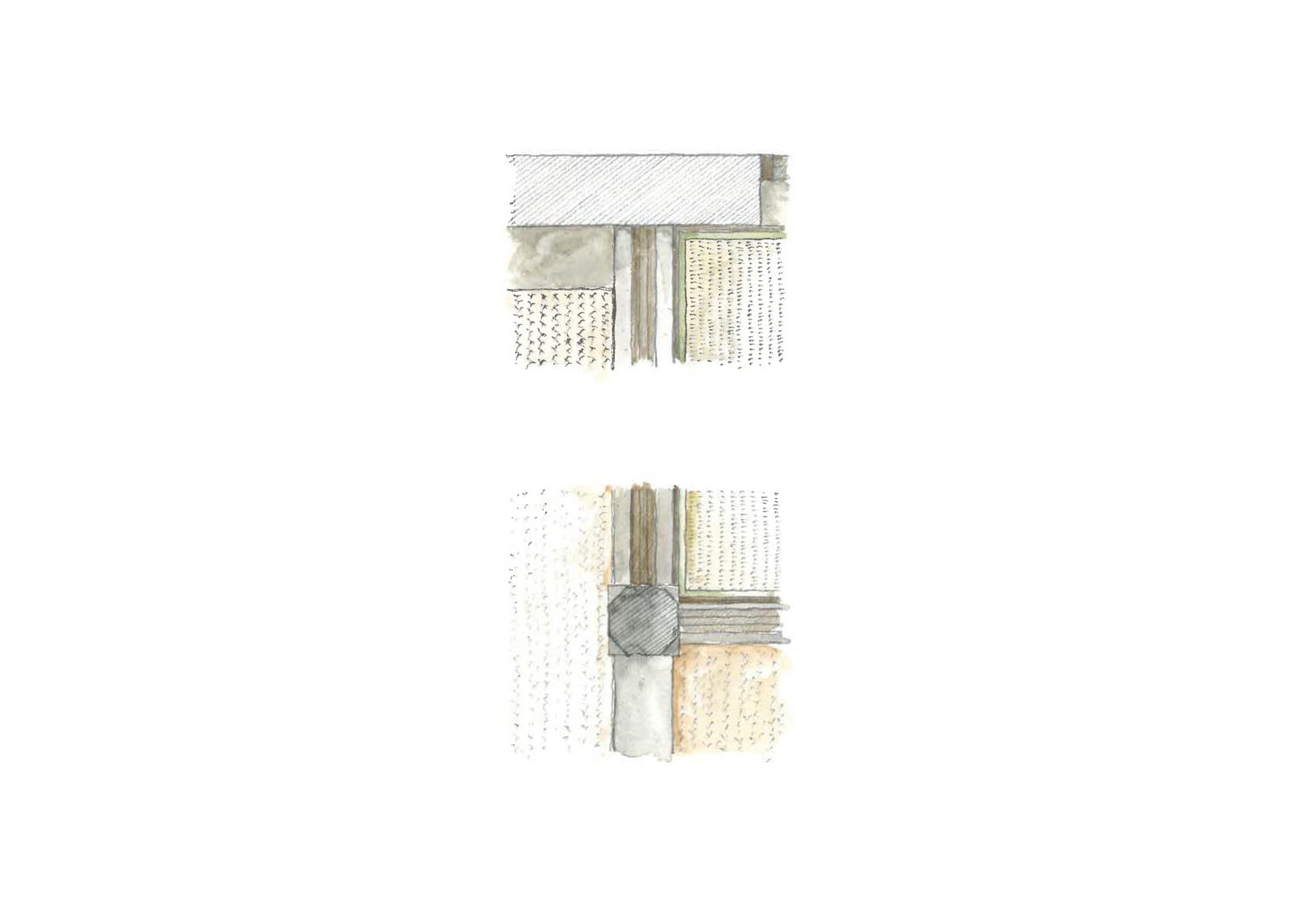

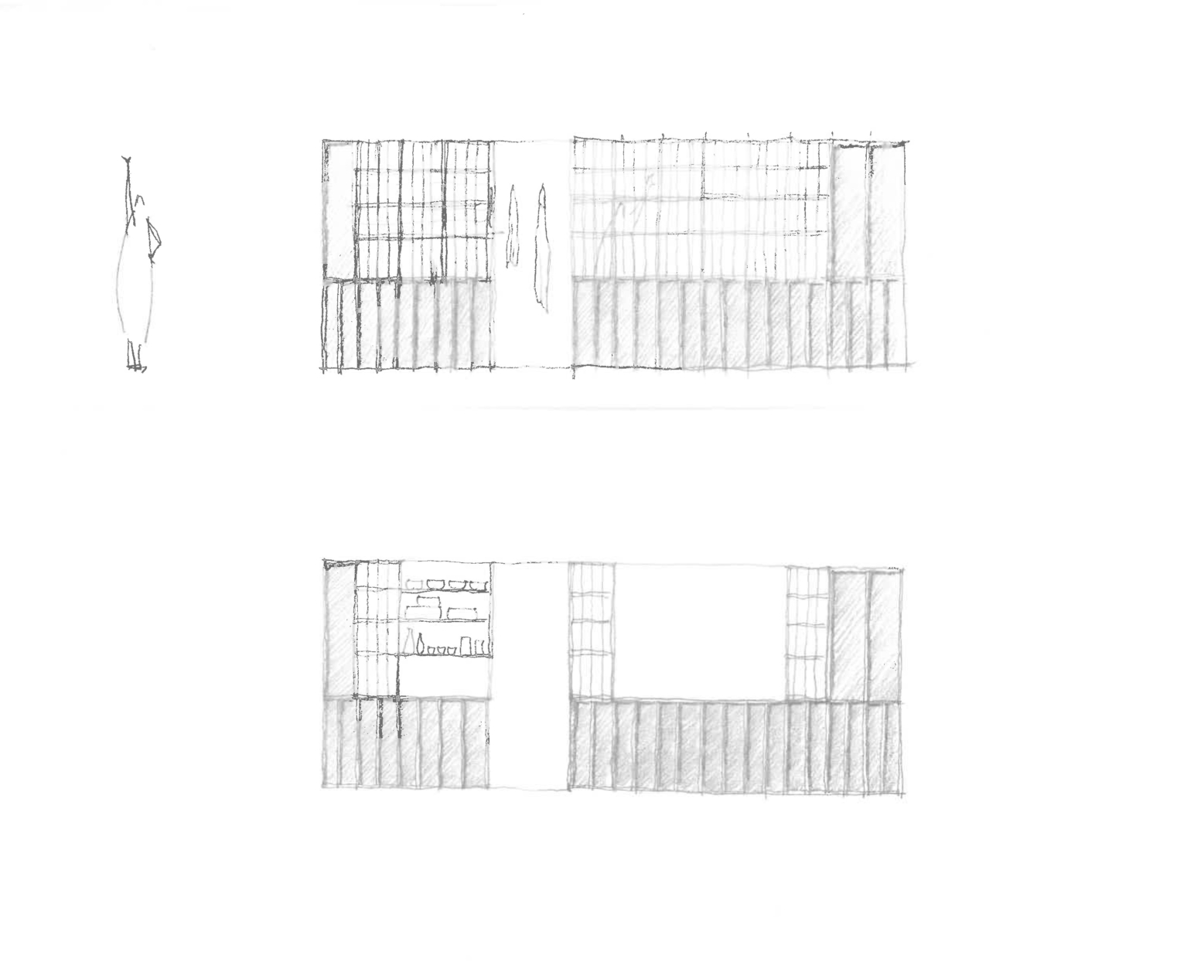

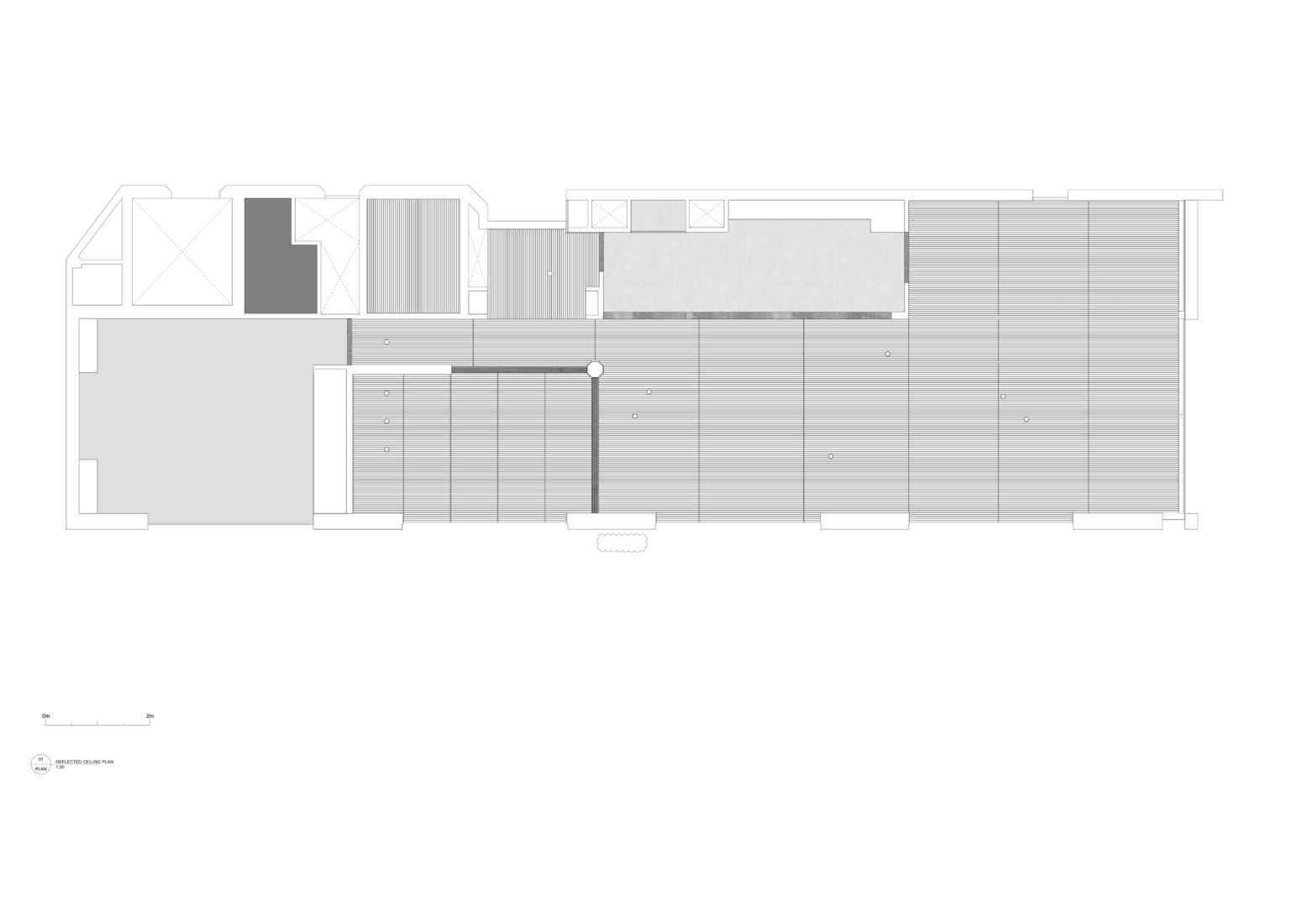

Spaces are defined more subtlety through architectural devices such as floor texture, screens and columns rather than walls, doors and functional programmes. This along with a palette of materials rich in texture aims to create a warm and peaceful ambience high in the City of London. The ceilings in all the main living rooms are lined in strips of solid cherry. Walls have been finished in a clay plaster with straw binder for added highlights and texture.

Client’s View

Embarking on this project, we knew that the strong character of the Barbican itself would be an inevitable presence. Still, we wanted a design which reflected our own life experiences, chief amongst these the many years spent living in Japan, followed by a similarly long period in Scandinavia. Equally, we wanted a place where the various possessions we had acquired along the way — Danish furniture, Japanese lamps, Swedish paintings, Korean pots — could easily co-exist.

We did not care much for what has become the standard ‘modernist’ open-plan look of recent Barbican flat renovations, in which everything is revealed the moment one steps in, like a New York loft or a WeWork office. We were more interested in things which are occluded, blocked, hidden, only to be discovered gradually. A completely stripped-out and empty flat looks strangely small. Screens, panels, columns, sliding doors, blinds: all these paradoxically add space by imposing structure. There is a temporal element as well: a Japanese or Korean house is experienced not all at once, but by stages. The entryway, for example, is a world of its own: rich in function, neither an inside nor an outside space; visitors can often spend half the morning standing there, happily chatting to the resident, never entering or even seeing the interior. From the entryway, turn one direction and an inner corridor leads to a closed sliding door, turn the other direction and a column obstructs your way into the inner part of the home. All the elements just described are present in t-sa’s seemingly simple design for the Barbican flat.

Passing from layout to materials, it is an accepted truism that a plain white ceiling is best for creating a feeling of space and light, mimetically alluding to the sky above us, just as wood or concrete flooring alludes to the earth below. In fact the opposite can be true, as Aalto showed us in his Villa Mairea, and as t-sa has realised here. Dense, dark, slatted, low: precisely-aligned unidirectional ceiling timber leads the eye away along the axis of the living space, creating an unexpected feeling of height and breadth. Continuing this radical inversion of the usual narrative, woven wool, the colour of pale clouds, covers the floor.

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon optimistically included large outdoor balconies on the ends of their Barbican tower block flats (following the lead of le Corbusier in his Cité Radieuse, but cheerfully ignoring the fact that the Cité Radieuse is sited in Marseille, not London). Early marketing literature showed happy couples sharing a picnic on their balcony in the warm evening light. In reality, virtually no one except the occasional exiled smoker uses these chilly and excessively windswept spaces for more than about five minutes. We deliberately selected a flat which had the end balcony enclosed and incorporated into the internal living space (such alterations were possible before the building was listed in 2001), leaving only the long narrow balcony along the side. In Japan and Korea flats often have balconies, but they serve as intermediate zones between outside and inside, not as a place to spend time or to look out from. In Asia, we were bemused the first time we came across an apartment block with a magnificent view of the Pacific Ocean: all the ocean-facing balconies were closed off and filled with drying laundry. It was then we understood the truth of what Tanizaki has written in In’ei Raisan: living spaces are essentially inward-looking and shadow-filled, places where precious objects (people included) can glow brightly. If you want to look at the ocean, you can go outside.

Encounter of Languages

The new apartment project at the Shakespeare tower in the Barbican developed through the initial conversations with its new owners, who previously had lived in Japan for many years.

Their knowledge of Japanese culture, custom and language is extraordinary and their experience of living there informed much of the design aspiration.

For our team that comprised Haruka Nogami (a Japanese architectural assistant – lead designer) and Edward Pepper, Giacomo Pelizzari and I, this has meant a project where we were challenged to explore the traditional Japanese architectural language meeting the concrete and timber structure of the modernist Barbican.

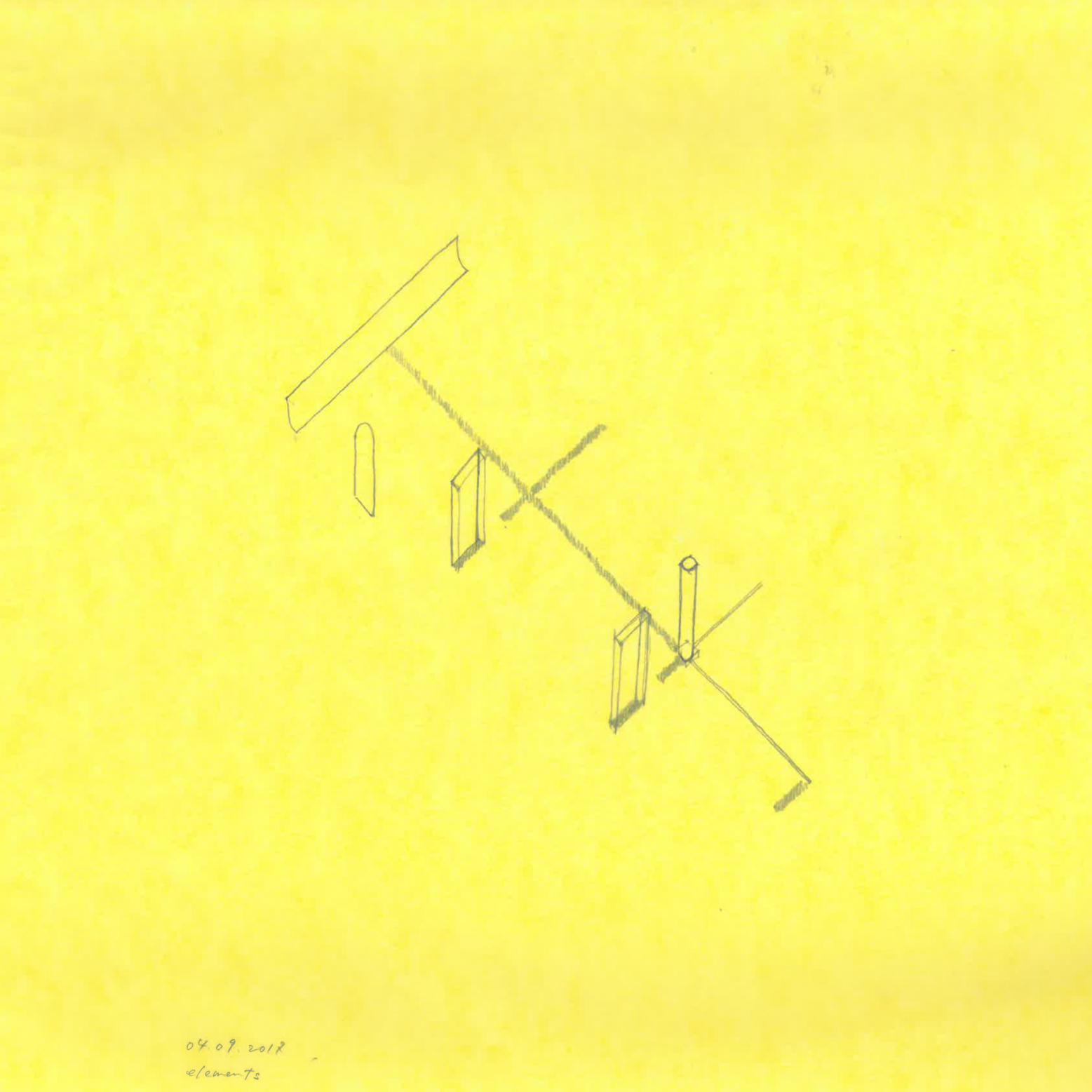

For our inspiration, we looked towards many of the early Modernist Japanese architects, who were dealing with the similar issues of identity when the European Modernism was entering Japan at rapid speed. Amongst these architects, we found the work of Seiichi Shirai particulary complex and interesting. Shirai lived in Germany, initially studying philosophy. Later, when he returned to Japan, his work seemed to be about working with both the traditional Japanese architectural and European classical language, but aiming to transcend both. For, Shirai, his architecture was neither Japanese nor European – but of his own.

We enjoyed working with the conflict of lighter, ephemeral language of timber screens, approximately but precisely laid out Arai-dashi stone pebble entrance floor, tatami mats against the raw, and weighty mass of the Barbican concrete walls, existing arched fire escape door, as well as the magnificent panoramic view of the City of London outside.

Particular efforts were made with the placement of non-structural terrazzo column that sits in the centre of the plan hugging the tatami laid Japanese room. Inspired by Shirai’s project at Sekisui-kan in Shizuoka, we made a gesture that this non-structural column could act as the bridge between the two conflicting language of this interior architecture. Columns in Japanese houses are also very symbolic. Shirai was obsessed with columns throughout his architectural career. Here, at the Barbican, we composed the terrazzo band that were laid around the perimeter of the floor spaces and connecting with this central column. Terrazo demarks each space and the material raises itself to encase the timber frame and the tatami mats.

The light that comes through the restored original timber framed windows reflect onto the perimeter terrazzo flooring and create a shimmering water like edge to this whole space. The terrazzo is also very similar in colour to the external terrace concrete floor, hence creating a seamless edging detail. Softer carpet is laid recessed into the floor for the living spaces.

Corridor that links the main living spaces onto the more minimal bedroom is accentuated in its length and width through the gently diffusing timber screens and the slightly glossy narrow black tiles in the bathrooms.

The resulting architecture does not belong to Japan, the classicism nor any specific time. It is a site and client specific architectural dialogue in language, tradition, renovation and ultimately, a spatial drama that is borne out of a gentle, yet conflicting encounter of language of the details in a small universe, inside a tower in London.

Takero Shimazaki

t-sa Team: Takero Shimazaki, Haruka Nogami, Edward Pepper, Jennifer Frewen, Giacomo Pelizzari

Photographs Anton Gorlenko